Monumental Proust Armchair

Alessandro Mendini

With a 2 x 2 cm square, you can cover the entire surface of the world, just like King Midas who turned everything he touched to gold.

Alessandro Mendini

Mendini was a key figure in the history of Bisazza – an ambassador, an instigator, and the firm’s artistic director from 1995 to 1999. When he took over the position, his avowed aim was to bring a new perspective to mosaics. At the time, he claimed their use had been “relegated to mosques or the swimming pools of Miami.” He not only employed them in his own projects, whether it be the Paradise Tower in Hiroshima or the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands, but also initiated collaborations with other designers and artists.

His works in the Bisazza Foundation are particularly noteworthy for their prodigious size. “This has led to a sort of dimensional paradox,” he notes, “where the object has lost any function and is almost exclusively a visual work, a work of art.”

The rest of Mendini’s career speaks for itself. He is recognized not only for his architecture and products, but also as one of the great theoreticians of design. He directed both Casabella and Domus, was a member of the Global Tools and Alchimia design groups, and collaborated with numerous other brands, such as Hermès, Cartier, and Venini.

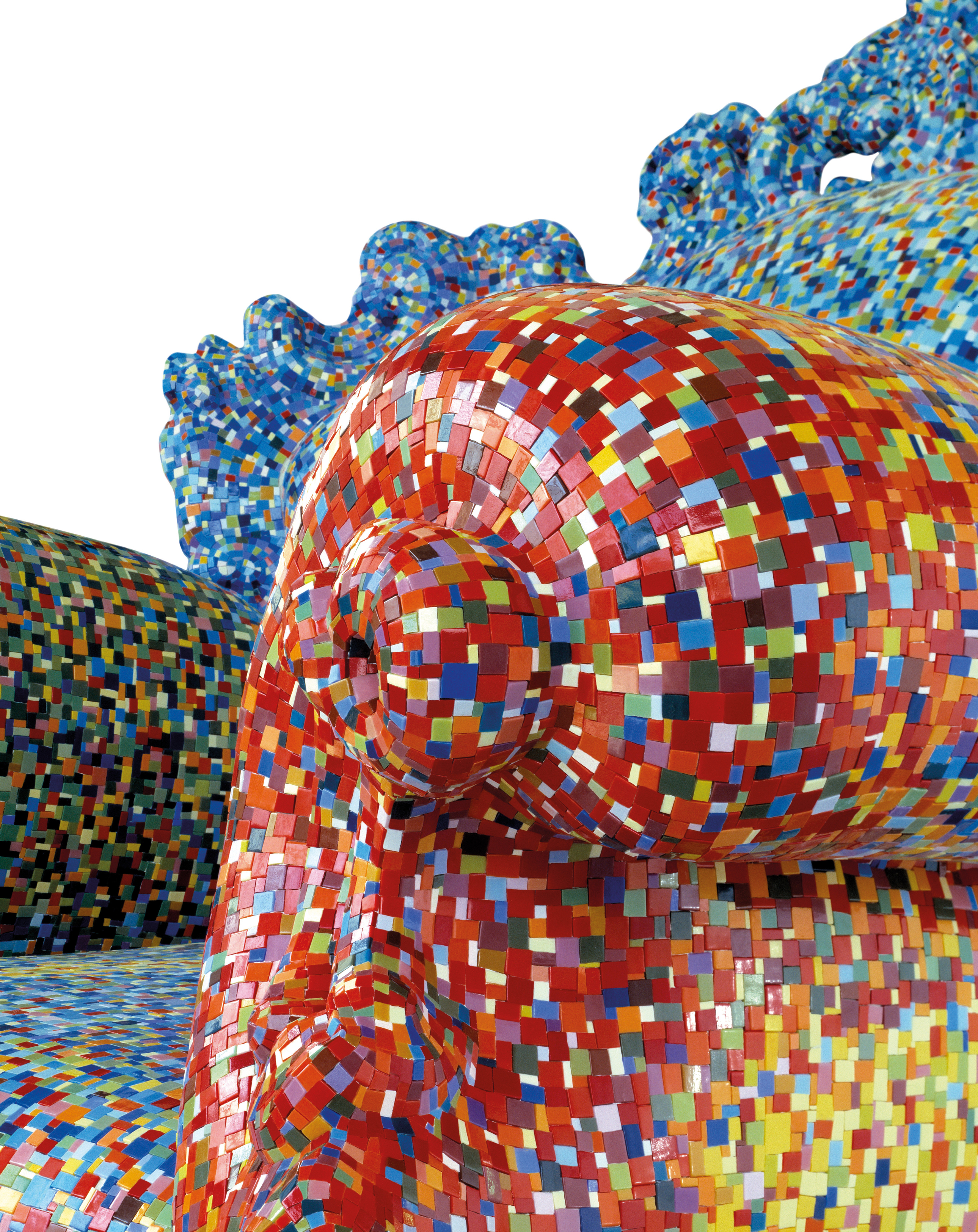

I believe that by now my piece entitled Proust Armchair is pretty well known by a lot of people. It is a romantic and baroque chair upon which infinite hand-brushed strokes of polychrome colours have been applied using a technique called divisionism. These brushstrokes cover the whole armchair, its fabric and its wooden flourishes.

It is a redesign. In fact, it is the result of a collage made up of a fake antique armchair and the detail of a meadow painted by the French artist Signac.

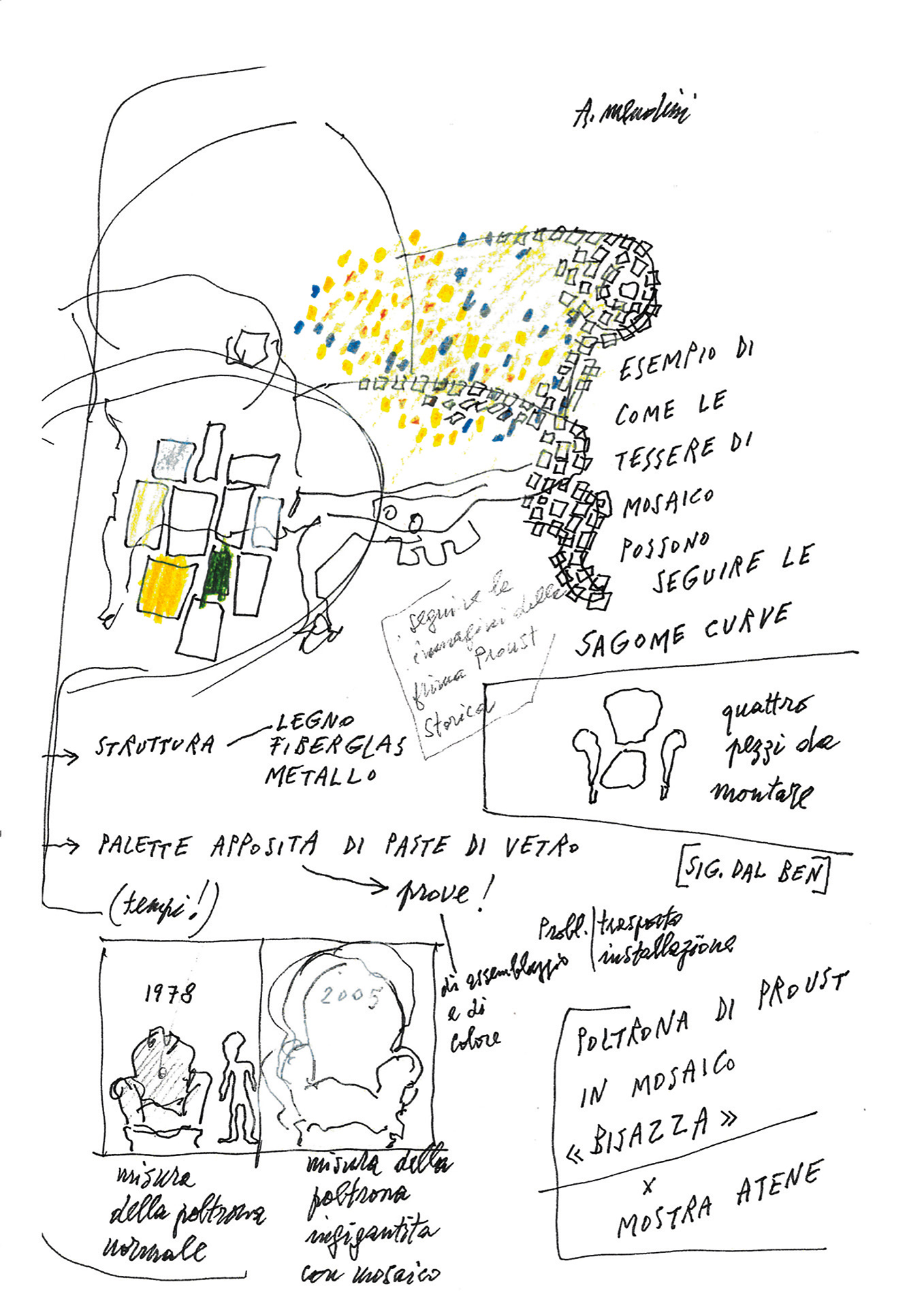

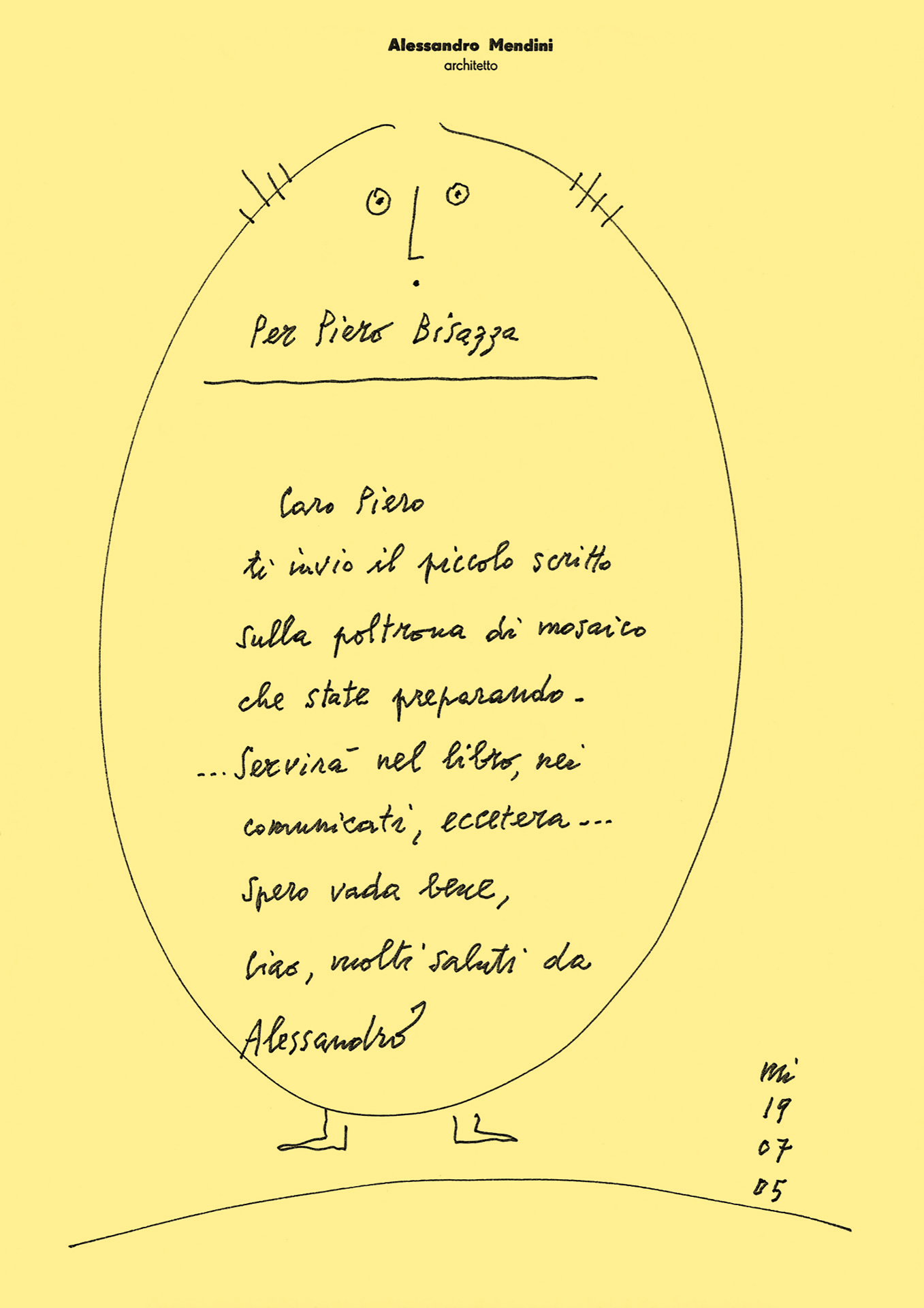

Since 1978 the Proust Armchair has been made in a succession of variants in new colours and materials. It has even been made in ceramics and bronze, and has travelled the world over. I had been nursing a secret dream for quite some time. It was to see the Armchair become big, very big – oversized. Enlarged so much that it would turn into a monument, an urban symbol.For the 2005 Art of Italian Design exhibition in Athens, there was the desire to place a macro-object in the street in front of the Museum: a piece made of that fabulous divisionist material called glass mosaic. Maybe a small tower, a kiosk, a very Italian souvenir. ‘Make an enormous Proust Armchair,’ Piero Bisazza suggested, guessing the gist of my unexpressed dream and giving it life. This collaboration of ours, with me as the designer and Piero as the industrialist, is one based on continuous and precise understanding. ‘All right, I will,’ I answered.

The project was a difficult and complex one in many ways: Statically, logistically, in its materials, the different types of glass and their colours and combinations. It was a virtuosic job that needed to be developed with manual techniques in the Bisazza factory.

Now, lo and behold, a Monumental Proust Armchair exists too.

It is no longer just an armchair; it is a sculpture and maybe even a piece of architecture. Its multicoloured glass surface brings the expressive intention that was born with the first Armchair to an extreme limit: that of imagining something, an unreal and pulveraceous nebula, an immaterial mirage of energy. Pointillism gives way to visual fragmentation and recomposition of matter.

Alessandro Mendini